… A blinding red light passed through the blanket, but it was pitch dark in the cave. They huddled in the farthest corner and hugged tightly. A hail of meteoric stones drummed on the bathtub, which covered the hole in the ceiling from the outside. The mountain shook and trembled, and the comet howled as if it was mortally frightened. Or maybe it was the Earth that was screaming with fear? They lay motionless for a long time, clung tightly to each other. The echoes of collapsing mountains and cracking Earth rumbled outside. The time was passing by terribly slowly, and each of them felt so lonely in this world.

Tove Jansson, “Comet in Moominland”

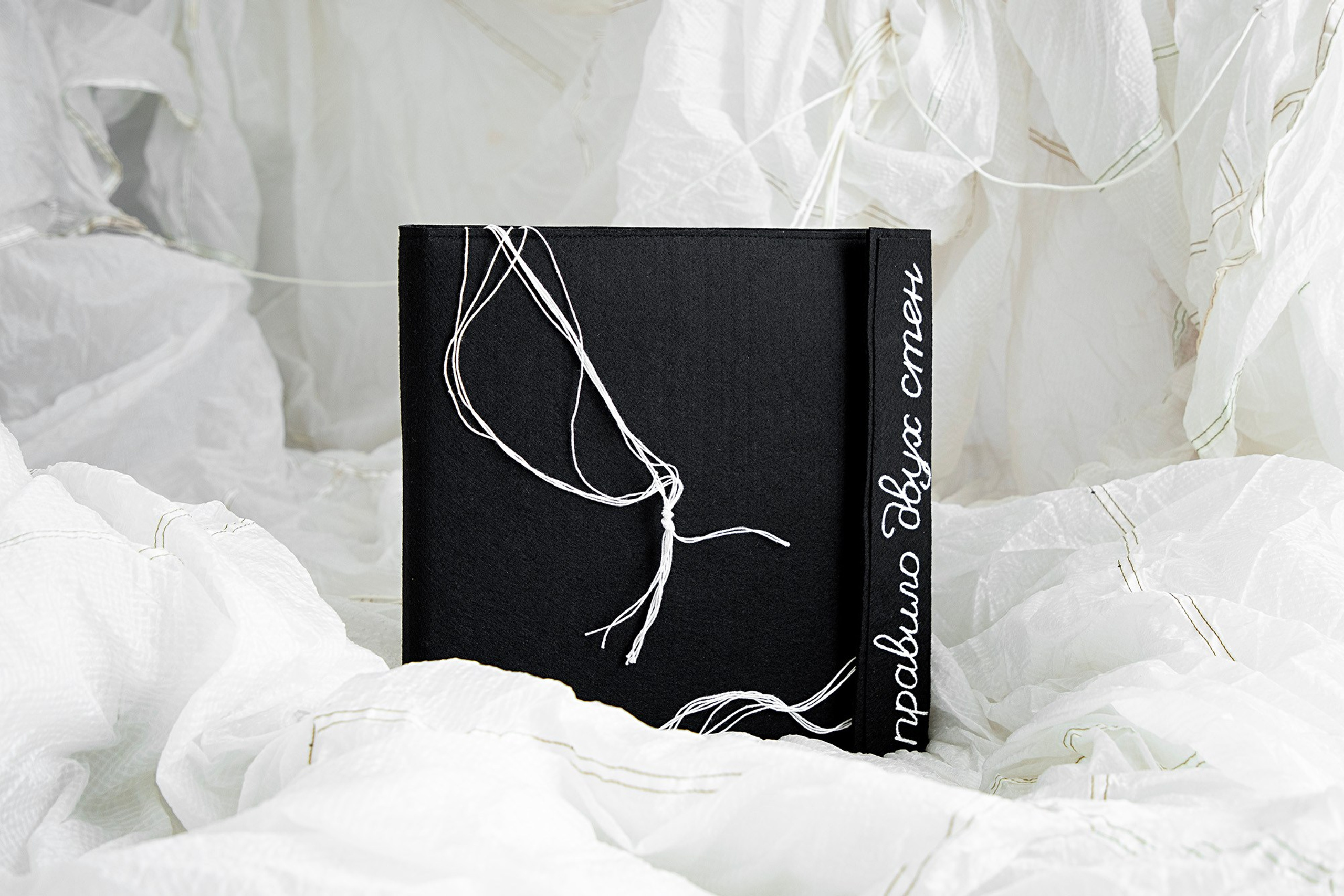

UNDER THE DOME (2013–2018)

Installation, photography, sculpture, objects, ready-made, archive, sound

Amazement and delight of discovery weren’t first — they flooded my feelings later. Initially there was fear. It came with a searing flash that bleached the urban landscape and seemingly erased time. The horizon tilted, concrete walls started trembling, and shards of broken windows rushed to the ground like a swarm of wasps. Many days after I’ll be carefully looking under my feet, avoiding the glass scattered by the blast wave and trying to distinguish the fragments of the broken dome.

Transparent, yet seemingly so reliable, it protected the planet from contact with а dark block of timeless space. This barrier no longer exists. From now on I will always realize how fragile it is, how fast thin fractures can appear on its surface. How rapidly its fragments can be scattering around. They dig into the landscape, throw up the grass and clods of soil, cut tree trunks and twist metal. They pass right through the walls and foundations of the houses, settle on the bottom of lakes and rivers. The damaged landscape is shriveling and giving off fumes but swallows these fragments. Fresh green shoots wrap the riddled earth, creating new outlines of the landscape

Decades after, nothing will reveal the traces of the once-broken dome. Only visual evidence of Chelyabinsk meteorite that recorded the incident will remain.

And scientific research will be preserved. But not the landscape. The landscape will forget everything. It has already acted like this more than once. Following two meteorites in May of 1891 the fragments of the dome dived into the factory pond of Nyazepetrovsk and the river Nyazya. In August of 1909, they burned simultaneously with a night meteor that that swept over Chelyabinsk. In the 1910s and 1920s, they were dispersed along the Yetkul and Yemanzhelinsk districts. In 1933 they crossed out the rising dawn sky with a broken scarlet line and disappeared on the border of Chelyabinsk and Kurgan regions, near Staroye Pesyanoye.

There will be a small layer of evidence in archival cases, in photocopies of provincial newspapers, on the last pages of Soviet periodicals (alongside with notes about fruit and vegetable experimental stations), in publications of specialized journals or in local lore sketches. But all material traces will be absorbed by the landscape. The earth seems to be striving to calm down the fear which appeared with another collapse of the dome.

The outlines of plains and forests are too large, too impersonal, too anonymous. They don’t offer places and objects available to that dimension where a person could see recognizable markers of past events. That is the reason why it is impossible to determine which of the dried-up small tributaries of the Uvelka river near Krasnogorskiy became a haven for a meteorite. It was wanted by historians in November 1926 but was probably used by the locals for some farm building in the nearest village. It seems unattainable to find a house in Selezyan village of Yetkul district in Chelyabinsk region, which foundation was made up of fragments of another 10-pood meteorite which fell in the fields in the early 1910s. Beyond our reach are the signs of the Katav-Ivanovsk bolid which fall in 1941. Its detection was prevented by the start of the Great Patriotic War.

I walk for miles across the fields and coastlines inspecting the remains of old structures. I seek for some relevant points on the map that could keep memory of the meteorites and preserve the traces of the previous collapses of the dome. In most cases I am not certain about the location of places mentioned in the archives or rare newspaper publications. Moving across the landscape, I do not find any signposts or memorials. I only try to guess whether the destroyed house, or a funnel in a meadow, or a thicket of reeds, or a cracked mountain is that wanted territory. I outline the surrounding landscape once again, as if hoping that in case it could be open as a tin can, if I could find any lost traces, then the fear might go, and the dome would be restored above my head.

However, it is not going to happen.

2018