BAKAL (2016)

Video documentation of two performances, photographs, installation, video, sculpture

Three rows of primary school children. There are several kids around me on this photograph whose German surnames I will misspell on the back side of the picture to remember them. Back in the 90s some families of my classmates began packing their belongings. The mothers and fathers of my friends were my parents’ colleagues in a military town in the north of Kazakhstan. I was perplexed, why did they say that they were returning to their homeland? I spent my whole childhood before moving to Russia surrounded by the Germans. However, I never wondered about the reasons of such neighborhood then.

Years later I found out about Bakalstroy-Chelyabmetallurgstroy Corrective Labor Camp, which existed in Chelyabinsk on the territory of Metallurgichesky District, in short — Bakallag. I finally managed to figure out the logic of foreign surnames’ presence on the back of my childhood photograph. These names belonged to the descendants of the Germans who were deported during and after the war to the Urals, Siberia, Altai, Central Asia — and to Kazakhstan. Starting with 1942, they were assembled into labor columns and sent to the system of corrective labor camps. In the circumstances of wartime, such camps turned from places for convicts into detention areas for free soviet citizens, who appeared to be the representatives of those nations that fought on the side of the Hitler Coalition. They were Italians, Finns, Romanians, Hungarians, but mainly Germans as their proportion in the contingent reached 86%. Their ancestors were invited by official policies of Catherine II. In the middle of the 20th century these citizens of the Volga Region were declared potential saboteurs and spies.

Mobilized people constructed roads, residential areas, and plants. In Chelyabinsk Bakallag prisoners often had to work without any project papers or estimates. A daily ratio consisted of 400-600 grams of bread, millet porridge on water in the morning, swill of rotten forest nettle silage at lunch and a bitter infusion of pine needles in the evening. As for the clothes, during the cold season the people wore jackets and shoes made from old tires. The easiest location to work was a stone quarry, the most difficult job was chopping trees in the woods. Any manifestation of dissatisfaction with the conditions of detention, even verbal, was perceived as pro-fascist and could inflict punishment up to execution. (Until the summer of 1943, Chelyabinsk GULAG contained 58% of all German prisoners sentenced to death that were held in the Ural Corrective Labor Camps.) Dying of exhaustion and diseases, the prisoners found their last resort in unmarked mass graves behind the slag dumps of metallurgical production.

After more than seventy years, the events related to Bakallag camp have almost no reflection in the modern landscape of the city. Like thousands of other repressed soviet citizens, the German prisoners that were kept in special settlements until the 1950s remained outside of the post-war heroization framework, and overall, on the periphery of the commemorative processes in comparison to home front workers.

Collective memory does not tolerate ambiguity. It is more convenient for this kind of memory to reduce events to mythical archetypes. The traumatic experience of dozens of thousands of people is forced to overcome the society’s unwillingness to pay attention to the heroic stereotypes about it. In Chelyabinsk, as in many other zones of former Corrective Labor Camps that are scattered around the country, the memory of the survivors and the memory of the dead is fixed in rare formal memorial objects. However, in the same way as the transformed territories of Bakallag with its buildings and outlines of the former camp that are still preserved in some places (the boundaries of its three sections coincide with the existing colonies), they are deprived of symbolic aura of memory that would point to the past and comprehend it. They are just an extension of the universal oblivion. Still, oblivion has no healing power for historical traumas.

2016

REST, performance (video, 20:00)

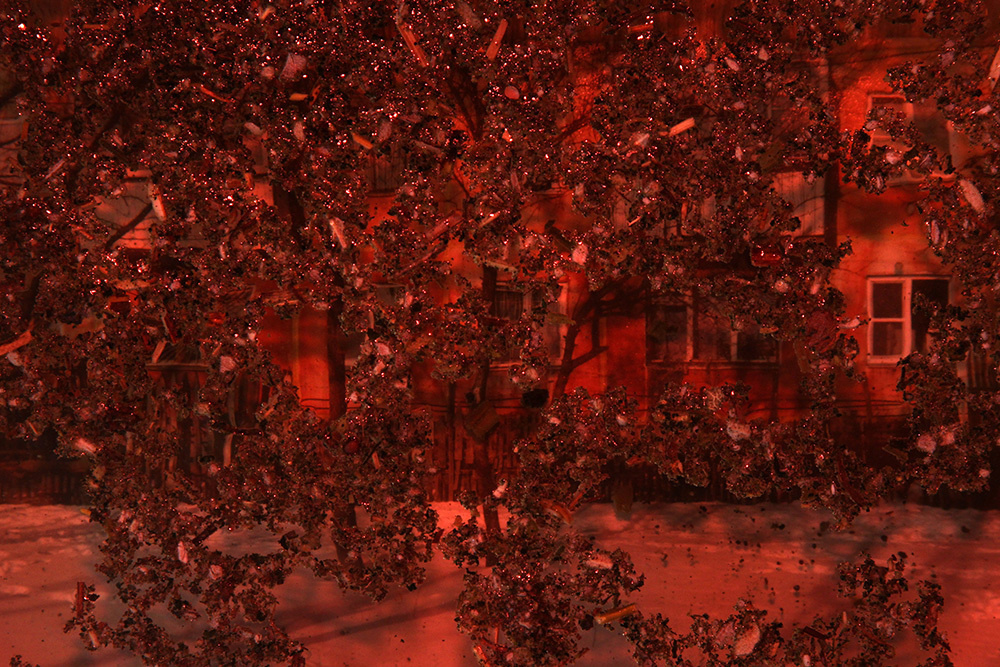

The performance was held on the territory of mass graves of Bakallag prisoners, in the open grave, preserved since the partial taking out of the remains in 2004. Chelyabinsk.

A QUARTER OF THE NORM, performance (video, 16:20)

The performance was held on the territory of the former Bakallag stone quarry, Chelyabinsk.

“Standing up to the ice-covered stone quarry, which was one of the most difficult working areas for the prisoners in the years of Bakallag, I planned to perform my own labour standard, beating a place on the perimeter and gradually moving to the centre. Several times I slumped into the water, wet my feet, broke my shoes. I sustained only eight circles. In the end, I stopped and fell into the snow. Eight circles. About a quarter of the norm. According to the rules of the labour camp it was supposed to be no more than 400 grams of bread.”